Early this week there was a disturbing contrast in the local press coverage in Guerrero of two stories that, on their face, were very similar. Both were originally published in the national daily Milenio and both involved allegations of institutional complicity with drug trafficking organizations (DTOs). The first was an article published on Monday that summarized accusations that have been published in the last year or so linking twelve municipal alcaldes to an assortment of DTOs (see http://bit.ly/11wcFjv). The second, published Tuesday, was an article that accused journalists of planting stories in local publications on behalf of Los Caballeros Templarios (see http://bit.ly/11G3iOh). The contrast in the coverage given to the two stories in local media outlets has been stark.

Story #1: The alcaldes Those who follow Guerrero will know that there was little or nothing new in the Milenio article that identified twelve alcaldes accused of links to DTOs. This was perhaps the first time the various the accusations were methodically organized into a single piece but the specifics of each of the cases were generally known from coverage in Guerrero’s local media outlets. The Milenio article ran on Monday and was summarized and/or excerpted widely by the Guerrero press on Tuesday. By the end of the week, all but three of the alcaldes named in the article had issued denials and these too were given coverage. (Two of the three are currently in federal custody facing criminal charges.) The alcaldes, alleged DTO affiliations, and their response to the charges were thus:

Ignacio de Jesús Valladares Salgado, the alcalde of Teloloapan accused of working on behalf of La Familia Michoacana. His denial and call for an open investigation of the charges was reported here: http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/228659.

Feliciano Álvarez Mesino, the former alcalde of Cuetzala accused of working for La Familia Michoacana. Ávarez Mesino is currently in detention in a federal prison in Tamaulipas.

Efraín Peña Damacio, the alcalde of Apaxtla accused of links to Guerreros Unidos. His denial and call for an open investigation of the charges was reported here: http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/228659 and here http://bit.ly/1r0wS7b.

Salomón Majul González, the alcalde of Taxco, accused of links to Guerreros Unidos. His denial of the charges and call for an open investigation was reported here: http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/229962.

José Luis Abarca Velázquez, the former alcalde of Iguala linked to Guerreros Unidos. Sr. Abarca is currently in detention in a federal prison in Tamaulipas.

Eric Fernández Ballesteros, the alcalde of Zihuatanejo accused of having links to a group of local Sinaloa and Beltrán Leyva operatives thought to have allied in opposition to Los Caballeros Templarios. Fernánez Ballesteros’ responded promptly on Facebook, denying all charges. His denial was also published late Monday in Milenio (http://bit.ly/1xS4edc) and again on Friday (http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/229962).

Francisco Javier García González, the alcalde of Chilapa accused of links to Los Rojos. His rejection of the accusation is here: http://bit.ly/1udyESe. His call for an open investigation was reported here: http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/229962.

Mario Moreno Arcos, the alcalde of Chilpancingo accused of providing support to Los Rojos. His denial and call for an open investigation was reported here: http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/228659 and http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/229962.

Crescencio Reyes Torres, the alcalde of La Unión accused of having links to Los Caballeros Templarios (specifically, to Servando Gómez Martínez, aka La Tuta). His denial and call for an open investigation of the charges was reported here: http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/228659.

Mario Alberto Chávez Carbajal, the alcalde of Heliodoro Castillo accused of having links to Los Rojos. His denial and call for an open investigation were reported here: http://bit.ly/1r0wS7b.

Leopoldo Ramiro Cabrera Chávez, the alcalde of Leonardo Bravo accused of having links to Los Rojos. To my knowledge Cabrera has not issued a public comment.

Rey Hilario Serrano, the alcalde of Coyuca de Catalán accused of providing support to Los Caballeros Templarios. His denial and call for an open investigation was reported here: http://bit.ly/1r0wS7b.

A somewhat surprising omission to the list was Elizabeth Gutiérrez Paz, alcaldesa of Tierra Colorada, of the PAN. Local media outlets have repeatedly published accusations of her links to Los Rojos. Had she been included all three major political parties would have had representation; as published only the PRI and PRD made the Milenio list. Gutiérrez’ alleged links to Los Rojos have nevertheless been regularly featured in local media reporting (e.g., see http://bit.ly/1qzJF5K and http://bit.ly/1p2VgJu).

Another omission was Saúl Beltrán Orozco, the alcalde of San Miguel Totolapan. He has lately been accused of supporting Guerreros Unidos (see http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/228623), an accusation he vigorously denied on Wednesday (see http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/229301).

The original Milenio article that cataloged the accusations of DTO complicity against twelve of state’s eighty-one municipal alcaldes received widespread press coverage and stimulated a statewide discussion of the issue. Story #2 was treated very differently.

Story #2: The journalists

On Tuesday Milenio published an article describing efforts by Los Caballeros Templarios to shape local media coverage of military activities in Tierra Caliente. Military deployments in Tierra Caliente have expanded in the wake of the Ayotzinapa incident and Los Caballeros Templarios is apparently feeling impinged upon as a result. In an effort to relieve the pressure, they apparently contrived a human rights denunciation against the Mexican army in La Joya, Cutzamala. They then planted articles in local media outlets about the fabricated incident. The hope was that the articles would generate public pressure on the army that would induce them to limit patrols and other operations. The planted articles named a specific military commander and drew vague allusions to the Tlatlaya massacre (see http://www.proceso.com.mx/?p=383033). Given the bad publicity the army has received in the wake of the Tlatlaya affair, Los Caballeros Templario’s plan stood (and stands) a reasonable chance of success.

Milenio published transcripts provided by intelligence sources of intercepted phone conversations between operatives of Los Caballeros Templarios and two local journalists, Israel Flores and Cecilio Pineda. The transcripts relate to conversations that, according to Milenio, took place on or shortly before November 11th. Articles by Pineda that report the La Joya, Cutzamala denunciation were published on November 12th by Agencia de Noticias Guerrero (http://bit.ly/1BQSWLw), the 13th in Despertar del Sur (http://bit.ly/11GLl2g) and the 14th by Notimundo (http://bit.ly/1HqMxXK). A final specimen with the same content, published under the name Zacarías Cervantes, appeared on November 13 in Pueblo Guerrero (http://bit.ly/1BQTscj).

Articles appearing in Flores’ name that addressed the alleged human rights violations in La Joya were printed in El Debate de los Calentanos on November 14th (http://bit.ly/1ueYXHR) and 18th (http://bit.ly/1xSj5o8) and El Sur on the same days (http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/227370 and http://suracapulco.mx/archivos/228593). Neither El Debate nor El Sur has issued a retraction nor offered other commentary on the Milenio article and the allegations it contains. Israel Flores has likewise made no public statement about the allegation.

Let us hope that we are dealing here with an anomaly. To recap, the local media treated the first Milenio article as significant news when it consisted merely of a compilation of months’ worth of rumor and innuendo that the local media had originally published. The second story received exactly no local coverage yet this was a genuine news story that broke new ground and that had a much more solid evidentiary foundation. It is a sad day when professional journalists would publish poorly sourced accusations of politicians colluding with DTOs, and to uncritically report on allegations of human rights abuses by the army, while ignoring much more powerful evidence of collusion with DTOs among their own ranks. There is a distasteful hypocrisy in this that is, well, discouraging.

I have written this post with some reluctance because it does not cast Guerrero’s local press corps in good light. It is hard to find heroes in Guerrero today and I like to imagine that local journalists rank among them. The work they do is vitally important to the anyone who values truth, justice, and peace.

October Homicides in Guerrero: FGE and GVP data compared

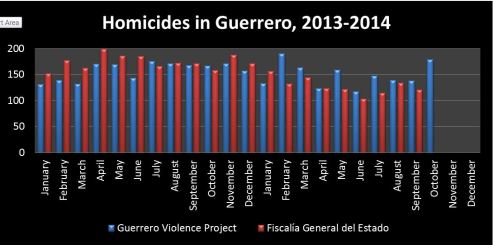

The number of registered homicidios dolosos in Guerrero in October was released by the Fiscalía General del Estado, or FGE, late yesterday afternoon (see http://bit.ly/1moTYql). They reported 118, three fewer than September. This was a stunning number. The GVP database has records of 189 homicides in October. As I noted in a previous post (see FGE Statistics and the Number of Dead in Guerrero, posted October 31), the GVP has recorded equal or higher numbers than reported by the FGE since February. Even so, the October numbers show the largest discrepancy between the two sources that has ever been recorded. The scope of the problem can be seen in the following chart:

As I noted before, the FGE generally reports multi-casualty incidents, including the discovery of clandestine cemeteries and mass graves, under a single case number. A multi-casualty event appears in their count of “homicidios” as one killing. In October the GVP recorded the following multi-casualty killings:

10/3 – 2 dead at pozoleria in Atoyac

10/4 – 2 dead at KM 212.4 on Highway 95 in Eduardo Neri

10/4 (and beyond) – 28 bodies excavated in six graves at Las Parotas, Iguala

10/5 – 3 dead in ambush in La Garita, Acapulco

10/5 – 2 dead at KM 189.5, Highway 95 in Eduardo Neri

10/7 – 2 dead at Las Antenas, in Coyuca de Benítez

10/8 – 2 dead in huerta near Río Chiquito, Petatlán

10/9 – 4 dead at Zihuatanejo-La Union highway at La Union corner

10/10 – 2 dead in Colonia Héroes de 47, Teloloapan

10/11 – 2 dead in El Jabalí, Coyuca de Catalán

10/11 – 2 dead at San Antonio de los Libres, Ajuchitlán

10/13 – 2 dead in Real Hacienda, Acapulco

10/14 – 3 dead in La Laja, Ajuchitlán

10/14 – 8 bodies excavated from fosa in Pueblo Nuevo, Iguala

10/17 – 2 dead near panteon in Igualapa

10/20 – 2 dead at the Central de Abastos, Acapulco

10/20 – unconfirmed report of 3 dead at Las Pilitas, Cocula

10/22 – 2 bodies excavated from fosa at Las Parotas, Iguala

10/27 – 3 dead in center of Cuajinicuilapa

10/27 – 2 dead in El Arenal, Azoyú

10/29 – 2 dead in Las Graviotas, Acapulco

10/29 – 13 bodies excavated from fosa near Ocotitlán, Zitlala

10/31 – 5 shot in bar near Las Cruces, Acapulco

This totals 98 bodies and 23 separate incidents. Were this to count as 23 rather than 98 the number of “homicides” appearing in the GVP database would equal 114, not 189. This number is remarkably close to the 118 “homicides” reported by the FGE.

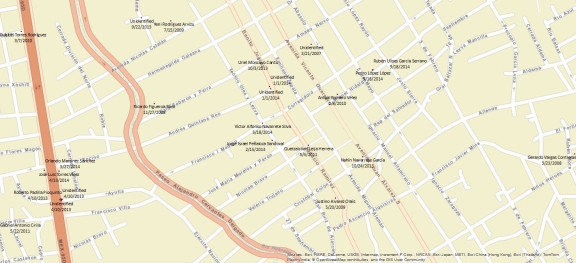

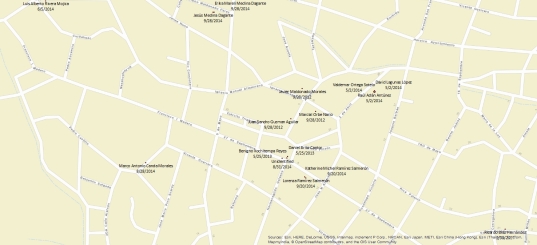

I say again, the FGE is not releasing data on individual homicide victims. They release data only on criminal investigations of lethal incidents. A much fuller accounting of homicides in Guerrero than provided by the FGE can be found in the tables associated with the GVP map. See it here: http://bit.ly/1wczk0u.